Urban Heat Island Mitigation

1. INTRODUCTION

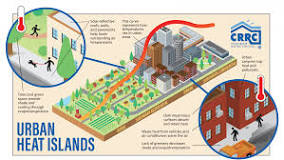

The urban heat island (UHI) phenomenon has been the subject of intense study over the past

several decades. Initial focus on the causes of the

UHI has led to a basic understanding of the factors

affecting heat island development and magnitude.

Related research into the effects of elevated urban

temperatures on air quality, energy consumption,

and human health has provided motivation for

reducing the magnitude of the UHI. The

information resulting from this body of research

has paved the way for development of strategies

to mitigate urban heat islands. These strategies

generally fall into two categories – increasing

urban radiation (reflectivity to solar radiation) and

increasing transpiration. The light radiation increases

are generally accomplished through high radiation

roofing and paving technologies. Increase in

evapotranspiration is accomplished through a

combination of decreasing the fraction of

impervious surfaces and planting vegetation in

urban areas (shade trees, vegetated walls, and

rooftop gardens/ecoroofs) for heat island mitigation.As urbanization intensifies, the phenomenon of urban heat islands demands targeted solutions. This project seeks to address the specific challenges of rising temperatures by meticulously examining successful case studies, engaging with domain experts, and crafting actionable recommendations. The motto, "Cooling our Cities, Nurturing Tomorrow's Habitats," signifies our commitment to not just immediate relief but also to the enduring balance of ecosystems and the well-being of urban dwellers.

The urban heat island (UHI) phenomenon has been the subject of intense study over the past

several decades. Initial focus on the causes of the

UHI has led to a basic understanding of the factors

affecting heat island development and magnitude.

Related research into the effects of elevated urban

temperatures on air quality, energy consumption,

and human health has provided motivation for

reducing the magnitude of the UHI. The

information resulting from this body of research

has paved the way for development of strategies

to mitigate urban heat islands. These strategies

generally fall into two categories – increasing

urban radiation (reflectivity to solar radiation) and

increasing transpiration. The light radiation increases

are generally accomplished through high radiation

roofing and paving technologies. Increase in

evapotranspiration is accomplished through a

combination of decreasing the fraction of

impervious surfaces and planting vegetation in

urban areas (shade trees, vegetated walls, and

rooftop gardens/ecoroofs) for heat island mitigation.As urbanization intensifies, the phenomenon of urban heat islands demands targeted solutions. This project seeks to address the specific challenges of rising temperatures by meticulously examining successful case studies, engaging with domain experts, and crafting actionable recommendations. The motto, "Cooling our Cities, Nurturing Tomorrow's Habitats," signifies our commitment to not just immediate relief but also to the enduring balance of ecosystems and the well-being of urban dwellers.

2. URBAN ENERGY BALANCE

As illustrated in Fig. 1 the urban energy

balance is driven by shortwave radiative input from

the sun. In midlatitudes the summer midday

shortwave flux may exceed 1000 W/m2

. As the shortwave radiation reaches surfaces in the urban

environment it is partially absorbed and partially

reflected. The ratio of reflected to total incoming

solar radiative heat flux is referred to as the

radiation. It is important to note that solar radiation

spans the frequency spectrum with most of the

sun’s energy content being concentrated in the

shortwave (0.4 to 0.7 µm) visible range. Hence

high altitude surfaces are generally characterized

by being light in color, or white. One key cause of

heat islands is that cities tend to have lower

albedos than the unbuilt surroundings. Compounding this albedo difference is the

underlying morphology of cities when solar radiation is reflected from a

street surface some of it escapes the urban

canopy, but some (depending upon the sky view

factor) is intercepted and partially absorbed by

exterior building walls.

Figure 1. A simplified model of the urban energy

balance including anthropogenic heating as a

source term (Qf).

The surface complexity introduced by urban

morphology also affects long wave radiative

exchange. All surfaces emit radiation as a function

of their absolute temperature (raised to the 4th

power). For surfaces with temperatures typically

encountered in the urban environment (e.g., 0 to

60 o

C) this energy is concentrated in the longwave

spectrum (peaking at wavelengths of about 10

µm). Longwave radiative emission is a key

mechanism whereby surfaces cool themselves at

night. In an urban setting, however, longwave

emission from one surface is often intercepted by

many other urban surfaces. The net effect is that

urban surfaces with their reduced sky view factor

tend to cool off slowly at night.

Another key component of the urban energy

balance is the prevalence of impervious surfaces

and general lack of vegetation in urban settings.

The complexity of urban canyons also has a

complex effect on localized wind speeds, and

hence on sensible (convective) heat loss of

surfaces. Convective heat transfer from some

surfaces is enhanced due to the wind channeling

effect through urban canyons.

As illustrated in Fig. 1 the urban energy

balance is driven by shortwave radiative input from

the sun. In midlatitudes the summer midday

shortwave flux may exceed 1000 W/m2

. As the shortwave radiation reaches surfaces in the urban

environment it is partially absorbed and partially

reflected. The ratio of reflected to total incoming

solar radiative heat flux is referred to as the

radiation. It is important to note that solar radiation

spans the frequency spectrum with most of the

sun’s energy content being concentrated in the

shortwave (0.4 to 0.7 µm) visible range. Hence

high altitude surfaces are generally characterized

by being light in color, or white. One key cause of

heat islands is that cities tend to have lower

albedos than the unbuilt surroundings. Compounding this albedo difference is the

underlying morphology of cities when solar radiation is reflected from a

street surface some of it escapes the urban

canopy, but some (depending upon the sky view

factor) is intercepted and partially absorbed by

exterior building walls.

Figure 1. A simplified model of the urban energy

balance including anthropogenic heating as a

source term (Qf).

The surface complexity introduced by urban

morphology also affects long wave radiative

exchange. All surfaces emit radiation as a function

of their absolute temperature (raised to the 4th

power). For surfaces with temperatures typically

encountered in the urban environment (e.g., 0 to

60 o

C) this energy is concentrated in the longwave

spectrum (peaking at wavelengths of about 10

µm). Longwave radiative emission is a key

mechanism whereby surfaces cool themselves at

night. In an urban setting, however, longwave

emission from one surface is often intercepted by

many other urban surfaces. The net effect is that

urban surfaces with their reduced sky view factor

tend to cool off slowly at night.

Another key component of the urban energy

balance is the prevalence of impervious surfaces

and general lack of vegetation in urban settings.

The complexity of urban canyons also has a

complex effect on localized wind speeds, and

hence on sensible (convective) heat loss of

surfaces. Convective heat transfer from some

surfaces is enhanced due to the wind channeling

effect through urban canyons.

3. MITIGATION STRATEGIES

The urban heat island exists in

both summer and winter seasons. In fact, it is

generally largest in the winter when it has some

beneficial characteristics related to reducing the

demand for heating energy. In summer, however,

the existence of the heat island has negative

implications in three key areas – air quality, human

health, and energy consumption for air

conditioning. It is this summertime heat island that

generally spawns an interest in mitigation.

3.1 Albedo

The primary surfaces in the urban

environment that are amenable to albedo increase

are rooftops, roadways, and parking lots.

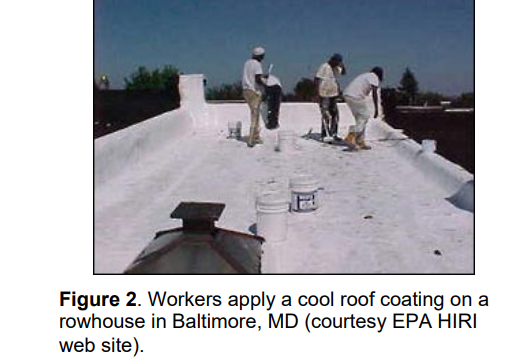

3.1.1 Roofing

There are a wide range of materials used for

roofing. For example, the Cool Roofing Material

Database (http://eetd.lbl.gov/CoolRoofs) compiled

by Lawrence Berkeley National Labs indicates that

light gray to white asphalt shingles with albedos

ranging from 0.22 to 0.36 exist in the marketplace.

For further

details regarding albedo, emissivity, and related

properties of a wide range of roofing materials the

interested reader is referred to the Cool Roofing

Material Database (http://eetd.lbl.gov/CoolRoofs).

Convective characteristics of roofing systems

can also play a role in their overall effectiveness

as a mitigation strategy. Roofing systems with

larger surface areas exposed to the outside air

(e.g. wood shake systems) can enhance

convection. 3.2 Direct and Indirect Effects of Mitigation

These mitigation strategies can have impacts

that range from localized effects to effects that are

manifested at scales as large as the city. For

example, implementing a high albedo roof on a

commercial building has the direct effect of

reducing the solar load on the building, and hence

reducing summertime energy demand for that

building. The same roof, however, also plays a

small role in the urban climate system as a whole.

Since the rooftop surface is cooler there is less

convective heating of the air that flows over the

building. The presence of many high albedo roofs

within a city can, in theory, indirectly benefit the

entire city through the combined air temperature

reduction effects. While the direct effects can

generally be measured the indirect effects must

typically be estimated through large scale

atmospheric model simulations (e.g., Sailor, 1998;

Taha et al., 1999; Kikegawa et al., 2004).

3.2 Direct and Indirect Effects of Mitigation

These mitigation strategies can have impacts

that range from localized effects to effects that are

manifested at scales as large as the city. For

example, implementing a high albedo roof on a

commercial building has the direct effect of

reducing the solar load on the building, and hence

reducing summertime energy demand for that

building. The same roof, however, also plays a

small role in the urban climate system as a whole.

Since the rooftop surface is cooler there is less

convective heating of the air that flows over the

building. The presence of many high albedo roofs

within a city can, in theory, indirectly benefit the

entire city through the combined air temperature

reduction effects. While the direct effects can

generally be measured the indirect effects must

typically be estimated through large scale

atmospheric model simulations (e.g., Sailor, 1998;

Taha et al., 1999; Kikegawa et al., 2004).

4. IMPLEMENTATION ISSUES

Cool Roofing: The commercial roofing market is largely composed of flat roofs that are relatively isolated from the public view. The residential market, however, with its traditional sloped roofs must consider aesthetics as a key implementation barrier .Darker roofs ranging from black asphalt shingles to wood shakes are often preferred by residential customers. This is likely due in part to their ability to hide dirt, moss, and other weathering characteristics. In many cases these darker surfaces also serve to help blend the house into the natural setting (e.g. cedar shingles).The Cool Roof Rating Council (CRRC) is an independent and non-biased organization that has established a system for providing Building Code Bodies, Energy Service Providers, Architects & Specifiers, Property Owners and Community Planners with accurate radiative property data on roof surfaces that may improve the energy efficiency of buildings while positively impacting our environment (www.coolroofs.org).

What are the Causes of Urban Heat Island?

Manifold increase in construction activities: For building simple urban dwellings to complex infrastructures, carbon absorbing material like asphalt and concrete is needed for the expansion of cities. They trap huge amounts of heat which increases the mean surface temperatures of urban areas. Dark surfaces: Many buildings found in urban areas have dark surfaces, thereby decreasing albedo and increased absorption of heat. Air conditioning: Buildings with dark surfaces heat up more rapidly and require more cooling from air conditioning, which requires more energy from power plants, which causes more pollution. Also, air conditioners exchange heat with atmospheric air, causing further local heating. Thus, there is a cascade effect that contributes to the expansion of urban heat islands. Urban Architecture: Tall buildings, and often accompanying narrow streets, hinder the circulation of air, reduce the wind speed, and thus reduce any natural cooling effects. This is called the Urban Canyon Effect. Need for mass transportation system: Transportation systems and the unimpeded use of fossil fuels also add warmth to urban areas. Lack of Trees and green areas: which impedes evapotranspiration, shade and removal of carbon dioxide, all the processes that help to cool the surrounding air. Click here for reference

Executive Summary:

In response to the escalating challenges posed by urban heat islands, our project, "Cooling our Cities, Nurturing Tomorrow's Habitats," has undertaken a meticulous exploration of strategies, technologies, and policies. Through a methodical approach encompassing case studies, expert interviews, and data analysis, our objective is to provide a tailored blueprint for mitigating urban heat islands and fostering sustainable urban environments.

This project employed a multifaceted approach to comprehensively address urban heat reduction. The following steps outline the project's methodology:

1. Case Studies: Successful examples of urban heat reduction projects from different cities around the world were analyzed. Specific case studies included the impact of green roof initiatives in Singapore and the implementation of cool pavement technologies in Los Angeles.

2. Expert Interviews: Insights from professionals in urban planning, environmental science, and policy-making were gathered. Interviews were conducted with city planners, architects, and environmental scientists to gain perspectives on the effectiveness of specific heat reduction strategies.

3. Data Collection and Analysis: Data from satellite imagery, weather stations, and urban sensors were utilized to assess the current state of UHIs and the impact of implemented measures. Temperature data in designated urban areas before and after the implementation of cool roof policies was analyzed.

4. Synthesis and Recommendations: Findings were consolidated to provide a comprehensive overview of effective strategies, successful case studies, and policy recommendations for urban heat reduction. A set of actionable recommendations for city planners was developed based on the synthesis of data, case studies, and expert insights.

CASE STUDIES

Case Study 1: Singapore's Green Roof Initiatives

Objective: To analyze the impact of Singapore's extensive green roof initiatives in mitigating urban heat.

Background: Singapore, known for its dense urban landscape, faced rising temperatures and increased urban heat island effects. In response, the city-state implemented a comprehensive strategy, focusing on the widespread adoption of green roofs. Green roofs involve planting vegetation on building rooftops, providing insulation and reducing heat absorption.

Implementation: The initiative involved collaboration between government bodies, urban planners, and private entities. Incentives were provided to building owners to install green roofs, and strict regulations were enforced to ensure new developments incorporated sustainable roofing practices. Additionally, public awareness campaigns were conducted to encourage community participation in green roof projects

Results: Temperature Reduction: Satellite imagery and on-site measurements demonstrated a noticeable decrease in surface temperatures in areas with widespread green roof adoption. Biodiversity Boost: The green roofs not only contributed to cooling but also fostered biodiversity, supporting the growth of various plant species and creating mini-ecosystems in the heart of the city. Community Engagement: The initiative garnered community support, with residents actively participating in maintaining and expanding green roof spaces.

Lessons Learned: Singapore's success highlights the effectiveness of a holistic approach, combining regulatory measures, financial incentives, and community engagement to address urban heat challenges.

Case Study 2: Los Angeles Cool Pavement Technologies

bjective: To examine the implementation and impact of cool pavement technologies in Los Angeles.

Background: Los Angeles, facing extreme heat and prolonged heat waves, sought innovative solutions to reduce surface temperatures. The city introduced cool pavement technologies as an alternative to traditional asphalt, aiming to reflect more sunlight and absorb less heat.

Implementation: Selected urban areas underwent pilot projects where traditional asphalt was replaced with cool pavement materials. These materials had higher solar reflectance, reducing the absorption of solar radiation and lowering surface temperatures. The project involved collaboration between city agencies, research institutions, and the private sector.

Results: Surface Temperature Reduction: Temperature monitoring indicated a substantial decrease in surface temperatures in areas with cool pavement technologies, particularly during peak heat hours.

Energy Efficiency: Cool pavements contributed to lower energy consumption in nearby buildings by reducing the need for air conditioning during hot periods.

Extended Lifespan: The new pavement materials demonstrated durability and a longer lifespan compared to traditional asphalt.

Lessons Learned: Los Angeles's experience underscores the importance of adopting innovative materials and technologies to combat urban heat, emphasizing the dual benefits of temperature reduction and enhanced energy efficiency. These case studies illustrate the diverse approaches cities can take to mitigate urban heat, showcasing the effectiveness of tailored strategies based on local conditions and challenges.

Expert Interviews:

Expert Interview 1: Dr. Maria Rodriguez - Environmental Scientist

Objective: To gather insights into the scientific aspects and challenges of urban heat mitigation.

Background:

Dr. Maria Rodriguez is a leading environmental scientist specializing in climate change and urban ecology. With a wealth of experience in studying the impacts of urbanization on local climates, Dr. Rodriguez's expertise lies in identifying effective strategies for mitigating urban heat islands.

Key Questions:

How do urbanization and land-use changes contribute to the formation of urban heat islands?

From a scientific perspective, what are the most promising strategies for reducing surface temperatures in urban areas?

How can data-driven approaches, such as satellite imagery and climate modeling, inform urban heat mitigation efforts?

In your research, have you identified any unexpected challenges or positive outcomes related to urban heat mitigation strategies?

Expected Insights:

Dr. Rodriguez's interview is expected to provide a scientific foundation for understanding the mechanisms behind urban heat islands and offer insights into cutting-edge strategies based on empirical research.

Expert Interview 2: Mr. James Thompson - Urban Planner and Policy Expert

Objective: To gain insights into the practical challenges and policy considerations in implementing urban heat mitigation strategies.

Background:

Mr. James Thompson is a seasoned urban planner with a focus on sustainable development and climate-responsive urban policies. With experience in both public and private sectors, he has been involved in the development and implementation of policies aimed at creating resilient and cool urban environments.

Key Questions:

What role do urban planning and policy play in mitigating urban heat, and how have you seen this evolve over the years?

Can you share examples of successful policy interventions that have effectively reduced urban heat in specific cities?

What challenges do urban planners commonly face when implementing heat mitigation strategies, and how can they be overcome?

How important is community engagement in the success of urban heat mitigation policies, and are there notable examples where community involvement made a significant impact?

Expected Insights:

Mr. Thompson's interview is expected to provide practical insights into the challenges and successes of implementing urban heat mitigation policies, emphasizing the role of urban planning and community engagement in achieving sustainable outcomes.

These expert interviews aim to capture a comprehensive understanding of urban heat mitigation, combining scientific expertise with practical insights from policy and planning perspectives.

Synthesis:

Objective: Consolidate findings to provide a comprehensive overview of effective strategies, successful case studies, and policy recommendations for urban heat reduction.

1. Synthesis of Findings:

Objective: To distill key insights from case studies, expert interviews, and data analysis.

Data Synthesis:

Combine data from satellite imagery, weather stations, urban sensors, and community feedback.

Identify common trends and patterns in urban heat intensity.

Case Study Insights:

Extract lessons learned and success factors from the analyzed case studies.

Identify replicable strategies for diverse urban contexts.

Expert Perspectives:

Synthesize insights from expert interviews, considering both scientific and practical viewpoints.

Highlight expert-recommended strategies for effective urban heat mitigation.

Community Feedback Integration:

Integrate community feedback into the synthesis to incorporate qualitative insights.

Ensure the recommendations align with community preferences and experiences.

2. Comprehensive Recommendations:

Objective: Develop actionable recommendations for urban planners and policymakers.

Targeted Mitigation Strategies:

Recommend specific mitigation strategies tailored to the unique characteristics of each urban area.

Prioritize interventions based on the severity of urban heat islands in different locations.

Policy Guidelines:

Propose policy recommendations to encourage the widespread adoption of effective mitigation measures.

Advocate for zoning regulations, building codes, and incentives that promote sustainable urban development.

Community Engagement Programs:

Emphasize the importance of community engagement in urban heat mitigation efforts.

Recommend the establishment of community programs to raise awareness and encourage participation in mitigation initiatives.

Technology Integration:

Highlight the integration of innovative technologies, such as cool pavements, green roofs, and reflective surfaces, in urban planning and infrastructure development.

Advocate for the incorporation of smart city technologies for real-time monitoring and adaptive responses.

3. Adaptation Strategies:

Objective: Provide recommendations for adapting urban spaces to changing climate conditions.

Climate-Responsive Urban Planning:

Advocate for climate-responsive urban planning that considers future climate projections.

Encourage the development of green spaces, urban forests, and water features to enhance natural cooling.

Resilient Infrastructure:

Recommend the incorporation of resilient infrastructure that can withstand extreme heat events.

Consider the integration of green infrastructure, such as permeable pavements and green walls, to enhance cooling effects.

4. Collaboration and Knowledge Exchange:

Objective: Facilitate collaboration among stakeholders and promote knowledge exchange.

Stakeholder Collaboration:

Encourage collaboration among government bodies, private sector entities, and community organizations.

Foster partnerships for the implementation of multifaceted urban heat mitigation projects.

Knowledge Sharing Platforms:

Propose the establishment of knowledge-sharing platforms, conferences, and workshops.

Facilitate the exchange of best practices, research findings, and successful strategies among urban planners and policymakers.

Sustainable Goals

Goal 1: Sustainable cities and communities:

This goal emphasizes making cities, inclusive safe,resistant and sustainable.UHI mitigation techniques aim to contribute to this by improving urban environments, reducing heat stress and enahancing overall liviablity

Goal 2:Climate Action

UHI mitigation directly relates to facilate action by addressing the localized warming effects in cities, thereby reducing energy consumption for cooling, lowering green house gas emmissions and adapting to climate change

Goal 3: Good health and Wellbeing

UHI mitigation can improve public health by reducing heat related illness and improving air quality, contributing to better overall wellbeing in urban populations

Goal 4: Affordable and clean energy

Strategies for UHI mitigation often involve more energy ,efficient building designs and green infrastructure, aligning with the aim of energy access to affordable reliable sustainable and modern energy for all

Therefore these goals highlight the multi-faceted benefits and connections between urban heat islands mitigation strategies and border sustainable development objectives.

Data Collection and Analysis:

Objective:

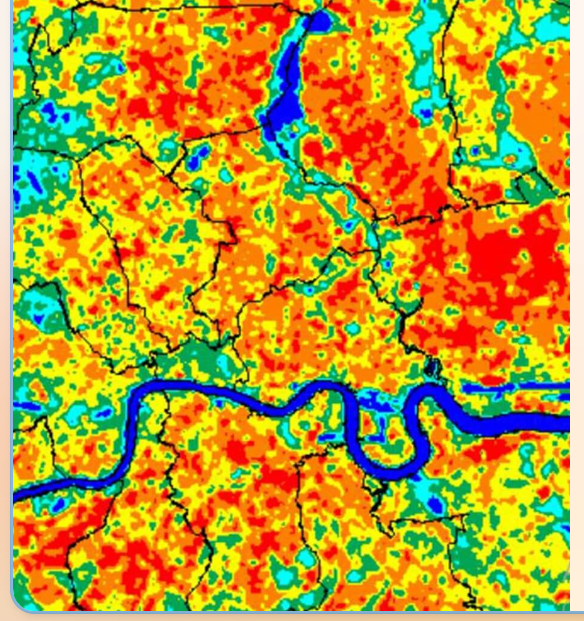

Utilize diverse sources of data to assess the current state of urban heat islands and evaluate the impact of implemented mitigation measures.1. Satellite Imagery Analysis:

Objective: To visually assess and quantify land surface temperatures in urban areas.

Data Source:

Obtain high-resolution satellite imagery from relevant time periods.

Analysis:

Use remote sensing techniques to identify and analyze land surface temperatures in target urban areas.

Compare temperature patterns over time to assess the effectiveness of implemented mitigation measures.

Expected Insights:

Identification of areas with high urban heat intensity.

Evaluation of temperature variations before and after mitigation interventions.

2. Weather Station Data Analysis:

Objective: To analyze historical weather data for correlations with urban heat trends.

Data Source:

Acquire historical weather data from local weather stations.

Analysis:

Examine temperature trends, including daily highs, lows, and average temperatures.

Identify patterns of heatwaves and their impact on urban heat islands.

Expected Insights:

Correlation between weather patterns and urban heat island intensity.

Identification of periods with the highest risk of heat-related issues.

3. Urban Sensor Networks:

Objective: To gather real-time data from urban sensor networks for localized analysis.

Data Source:

Deploy urban sensors strategically across target areas.

Analysis:

Collect real-time data on temperature, air quality, and other relevant factors.

Analyze sensor data to identify localized heat islands and assess the impact of mitigation measures.

Expected Insights:

Real-time monitoring of temperature variations.

Identification of specific urban areas requiring targeted mitigation interventions.

4. Community Engagement Data:

Objective: To incorporate qualitative data from community feedback and experiences.

Data Source:

Conduct surveys, interviews, or focus group discussions with residents.

Analysis:

Analyze qualitative feedback on perceived temperature changes and comfort levels.

Identify community preferences for specific mitigation strategies.

Expected Insights:

Integration of community perspectives into the assessment of urban heat mitigation success.

Identification of potential areas for improvement based on resident experiences.

5. Comparative Analysis:

Objective: To compare data sets before and after the implementation of specific mitigation measures.

Data Source:

Compile data from satellite imagery, weather stations, urban sensors, and community feedback.

Analysis:

Conduct a comparative analysis to assess the effectiveness of implemented mitigation measures.

Identify correlations between different data sets to refine mitigation strategies.

Expected Insights:

Quantitative evidence of the impact of specific mitigation measures.

Refinement of strategies based on data-driven insights.

Conclusion:

The data collection and analysis phase aims to provide a comprehensive and data-driven understanding of urban heat islands. By combining satellite imagery, weather data, urban sensor networks, and community feedback, the analysis will contribute to the synthesis of findings and the formulation of actionable recommendations for effective urban heat mitigation.DATA BASED ON MEDIA REPORTS

Why are our cities warmer than their suburbs and rural areas?

Why are our cities warmer than their suburbs and rural areas?

n a densely populated city is as much as 2 degrees higher than suburban or rural areas. A recent study from IIT Kharagpur called “Anthropogenic forcing exacerbating the urban heat islands in India” noted that the relatively warmer temperature in urban areas, compared to suburbs, may contain potential health hazards due to heat waves apart from pollution. Arun Chakraborty an author of the study said, “Our research is a detailed and careful analysis of urban heat islands in India. We study the difference between urban and surrounding rural land surface temperatures, across all seasons in 44 major cities from 2001 to 2017.” He further said, “For the first time, we have found evidence of mean daytime temperature of surface urban heat island (UHI Intensity) going up to 2 degrees C for most cities, as analysed from satellite temperature measurements in monsoon and post monsoon periods.” Other researchers from elsewhere have also noticed similar rise in daytime temperatures in Delhi, Mumbai, Bengaluru, Hyderabad and Chennai. We know of urban water lakes (as in Bhopal, Hyderabad, Bengaluru or Srinagar) which add pleasure and coolness, but an urban heat island? An urban heat island (abbreviated as UHI) is where the temperature in a densely populated city is as much as 2 degrees higher than suburban or rural areas. Why? This happens because of the materials used for pavements, roads and roofs, such as concrete, asphalt (tar) and bricks, which are opaque, do not transmit light, but have higher heat capacity and thermal conductivity than rural areas, which have more open space, trees and grass. Trees and plants are characterised by their ‘evapotranspiration’— a combination of words wherein evaporation involves the movement of water to the surrounding air, and transpiration refers to the movement of water within a plant and the subsequent lot of water through the stomata (pores found on the leaf surface) in its leaves. Grass, plants and trees in the suburbs and rural areas do this. The lack of such evapotranspiration in the city leads to the city experiencing higher temperature than its surroundings. Click here for refernce

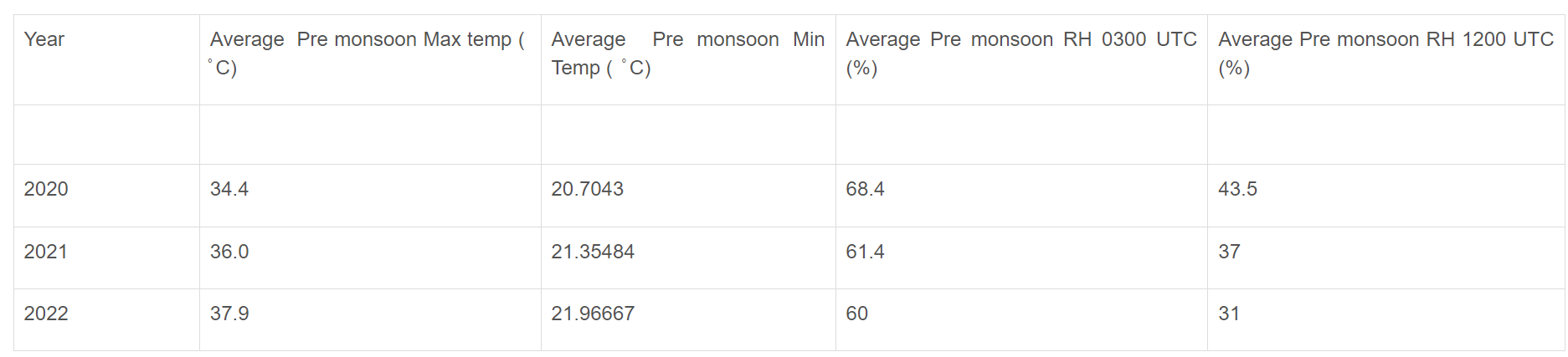

Government Data

Union Minister of State (Independent Charge) Science & Technology; Minister of State (Independent Charge) Earth Sciences; MoS PMO, Personnel, Public Grievances, Pensions, Atomic Energy and Space, Dr Jitendra Singh said, the steep rise in pre-monsoon surface air temperature, land surface temperature and relative humidity in Delhi/NCR off late is a cause of concern. In reply to a question in the Rajya today, Dr Jitendra Singh in a statement laid on the table of the House said, there has been a rise in Maximum and Minimum temperature over Delhi during Pre monsoon season during last three years whereas there is no such increase in Relative Humidity. The details of average values of maximum and minimum temperature and relative humidity (RH) over Delhi during the season for the last three years with respect to Safdarjung station are given below through the link: Government data